In the summer of 2020 I completed my PhD thesis, entitled ‘Imagining the Anthropocene: Contemporary Science Fiction Cinema in an Era of Climatic Change’.

While I have considered pursuing getting this published as a book, for me right now the most important thing is allowing folks to have access to the research, and be able to read/analyse/critique it as they see fit! After a few requests for access to the thesis in my inbox over the last few months I’ve decided to upload the PDF here for anybody who may be interested. Any feedback, dialogue or references from fellow eco-enthusiasts in the field would be very warmly received. I hope it’s of help or use to people’s thinking now, and in the future, as we collectively delve deeper into this troubling Anthropocene era.

Please find the PDF, and a brief chapter breakdown below.

Thank you!

Abstract & Chapter Breakdown

Chapter 1 – Introduction, Literature Review and Methodology

Introduction – 6

Literature Review – 17

Methodology – 48

Chapter Overview – 56

Part One: From the Technological to the Ecological

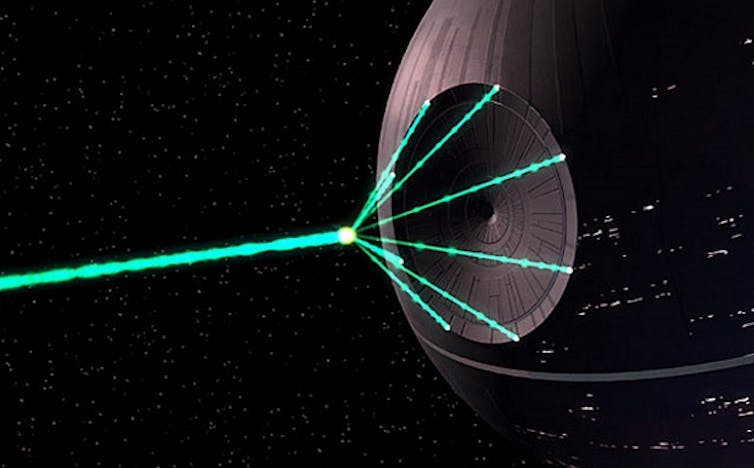

Chapter 2 – Changing Imaginations of Disaster: Different Death Stars

and Devastated Earths

Star Wars: From The Death Star-to-Star Killer Base and Back Again – 72

After Earth: An Imagination of Disaster for the Anthropocene – 85

Conclusion: Beyond After Earth – 107

Chapter 3 – Nonhuman Perspectives: Annihilation, Ecomonstrosity

and the Posthuman

The Terminator and The Thing: Technological and Ecological Posthuman

Forms – 117

Ecomonstrous Encounters in Annihilation – 133

From Ecomonsters to Zoe-Centric Posthumanism – 146

Conclusion: What Next for Posthuman Science Fiction Cinema 156

Part 2: Temporal and Planetary Imaginaries

Chapter 4 – Time Found and Felt in the Anthropocene: Folding Time in

Interstellar and Arrival

Cinema, Time, Modernity and The Anthropocene – 170

Time as Environment: Interstellar’s Folding Temporal Signatures – 176

Arrival, Interstellar and Transcending Temporal Flow – 192

Conclusion – 206

Chapter 5 – A Planetary Perspective: Melancholia, Another Earth and

Gravity’s Ecofeminist Sublime

An Ecofeminine Sublime in Another Earth and Melancholia – 222

Gravity’s World-With-Us – 233

Conclusion – 261

Bibliography – 270

Filmography – 279

The first part of this thesis, comprising chapters two and three, is entitled ‘From the Technological to the Ecological’. Both of these chapters display a movement in the genre from technological concern to ecological concern. Chapter two re-evaluates Susan Sontag’s claims made in her seminal piece, ‘The Imagination of Disaster’. In this Sontag argues that science fiction films are about disaster, specifically that of nuclear threat. A comparative analysis between the original Death Star from 1977’s Star Wars: A New Hope (Lucas, 1977) and the “new” Death Stars in Star Wars: The Force Awakens (Abrams, 2015) and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (Edwards, 2016) will be used to unveil a shift from a technologically grounded weapon, to an ecologically grounded weapon. This change, I argue, is emblematic of a wider shift in the genre wherein the environmental and ecological concerns of the Anthropocene begin to bleed into science fiction cinema’s disaster imaginary. This changed imagination of disaster is disclosed through a close textual analysis of After Earth, which is used as a centrifugal example of a series of films that similarly orient themselves around the complexities of living and dying in the Anthropocene. Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015), Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (Reeves, 2014), Snowpiercer and Interstellar are among these texts. After Earth can be seen to stage its imagination of disaster around humanity’s placement in an extreme Earth environment, a situation not dissimilar to our own. After Earth utilises deep-time, Earth history and unruly environments as the cornerstones of its disaster imaginary, all of which resound with the material and philosophical pressures of a warming climate. While not all science fiction films are engaged in this shift in representation, this chapter argues that the number of films it occurs across is representative of a changed focus in much 21st century science fiction towards ecological concerns.

Chapter three similarly argues that a representational shift from the technological to the ecological occurs, though in a much more anomalous fashion than its imagination of disaster. This chapter concentrates on the figure of the posthuman. It considers its historical representation in the genre as well as its uses for the ecological imperatives of our times. It demarcates two broad posthuman forms in the genre: one technological, the other ecological. Using The Terminator (Cameron, 1984) and The Thing (Carpenter, 1982) as respectively representative examples of these two types of posthumanism. It unveils the anthropocentric proclivities of both, unfit for the critical need to think “beyond” the human in the Anthropocene context. I argue that Annihilation reconciles the shortcomings of dominant posthuman imaginaries in the genre, using this text to point towards the slippery boundary between the human and the nonhuman when both are placed under alien environmental conditions. Through the writing of Alaimo, Rosi Braidotti, Cary Wolfe and Joanna Zylinska this chapter argues that Annihilation presents posthuman forms of pertinence to the pressures of the Anthropocene. It unearths a series of nonhuman, or what will be referred to as ‘ecomonstrous’, perspectives as a means of disassembling the anthropocentric proclivities of science fiction cinema’s historical posthuman figures. In doing so Annihilation operates as a unique text, gesturing towards the ‘trans-corporeal’ (Alaimo: 2010, 2) nature of human/nonhuman relations in, and out of, the Anthropocene context.

The last part of this thesis, comprising chapters four and five, is entitled ‘Temporal and Planetary Imaginaries’. Each chapter uses 21st century science fiction films to reveal a transformation in the representational mechanics of the 20th century’s temporal and planetary infrastructures. Both chapters contend that these representational changes are concomitant with the various ecological pressures and demands of the Anthropocene context. If Part One traced a movement from the technological to the ecological, this second section traces a movement from modernity to the Anthropocene. They do not suggest that the Anthropocene and modernity are necessarily separate entities, but do establish some clear differences between them. Chapter four is concerned with time, and chapter five is concerned with planets. Chapter four considers the temporal infrastructure of the Anthropocene, and argues that science fiction cinema is particularly well equipped as a device for mediating the epoch’s collapsed timeshape. Mary Ann Doane’s writing in The Emergence of Cinematic Time is used as a framing device for understanding cinema’s relationship with time, and more specifically the temporality of modernity. Doane argued that cinema of the early 20th century reflected the temporal changes of modernity (2002, 32). I will argue that certain science fiction films of the early 21st century reflect the temporal collapses of the Anthropocene. Using Interstellar and Arrival (Villeneuve, 2016) as case studies this chapter will consider the ways in which deep time, human time and various other types of time interact with one another. Where Interstellar lends time a geological quality, Arrival presents time through a nonhuman alien lens. In doing so these films provide platforms for considering time from other-than-human-or-Earthbound perspectives. They emphasise the crisis point of the human jumbled up with temporalities foreign to their own. In doing so these films reflect new senses of time found and felt in the Anthropocene. Following Chakrabarty’s logic, if the distinction between human history and geological history has collapsed (2009, 201) then so too has the distinction between human time and nonhuman time. This chapter unveils a collapsed time signature in these films, arguing that such a formation helps us to better experience the temporal infrastructure of the 21st century.

The fifth and final chapter ecocritically investigates the representational logic of picturing planets. It opens with a historically contextualised analysis of what are perhaps modernity’s most iconic images (Clark: 2015, 30): NASA’s Apollo Programme photographs of Planet Earth. This chapter considers the sublime aesthetic’s operation in planetary imagery, whether imaged by NASA or by science fiction. Through a comparative analysis of the sublime planetary imagery found in Another Earth (Cahill, 2011), Melancholia (von Trier, 2011) and Gravity this chapter unearths that the sublime’s recurrence in 21st century science fiction contains not just ecocentric principles, but also more specifically ecofeminist principles. Gravity is focused on in particular in this chapter. By reading the evolving relationship between its characters and the planet through Eugene Thacker’s conceptions of the world-for-us, the world-in-itself and the world-without-us (2011, 6) this chapter unveils a constellation of eco-perspectives converging around images of Planet Earth. Gravity’s ecofeminist re-modulation of the sublime allows new ways of understanding the various contradictions and intricacies at play in planetary imagery’s operation in the Anthropocene. It helps consider what sort of planetary perspective is arrived at through the various environmental and ecological demands wrought through anthropocentrically induced climate change.

This thesis is one of the first and most sustained critical reflections on the ties between science fiction cinema and the Anthropocene. It does not contend that these films offer flawless views of the conditions that produced, and are produced by, this epoch. Indeed, in the last two chapters in particular I am often critical of the problematic colonial and gender dynamics of the chosen texts. The point here is neither to revere nor condemn the films, but to signpost the ways in which they relate to the ethical, material and philosophical imperatives of our times. In moments of bombastic action and calm reflection alike the films selected for analysis convey an open and emphatic concern with environmental and ecological issues. As we navigate the difficulties of living on a dying planet, it is my hope that the thoughts offered herein will invite more future writing and consideration of science fiction’s placement in, and pertinence to, the environmental humanities. As a number of writers have already noted, there is something science fictional about the Anthropocene (Swanson, Bubandt and Tsing; Northcott; von Mossner; Morton; Haraway; Latour; Canavan and Robinson). It requires a sense of temporal and spatial extraction that is difficult to accomplish outside of the genre, it is as if we need science fiction to see and experience it. It should perhaps come as no surprise then that science fiction produced in the 21st century often reflects the ecological imperatives and pressures of this epoch. Conversely, what does come as a surprise is the lack of consideration given to science fiction cinema in ecocinematic writing or the more specific field of Anthropocenema (Kara: 2016, 9). This thesis contends that in order to effectively understand cinema’s relation to the Anthropocene science fiction has to be a central part of the conversation. Moreover, it suggests that science fiction should be more closely considered in ecocritical writing, both inside and outside of film studies. The off-handed nature with which many writers deploy science fiction films as quick referents is useful for this thesis’ research goals, but in other ways rather irksome. By closely considering science fiction through the Anthropocene, and the Anthropocene through science fiction, this thesis critically reflects on the ties that bind them together. Disasters are imagined differently, human bodies find themselves imbricated with strange nonhuman environments, cinematic time registers begin to collapse and the sublime aesthetic undergoes ecologically oriented transformations. By way of this set of interdependently considered observations, this thesis unveils not just what happens to science fiction in the Anthropocene context, but how science fiction provides new frameworks for analysing the Anthropocene itself.